The Pacers were saved by the Indiana community in the seventies

Imagine a world with no Indiana Pacers basketball. A world where the team has been uprooted to a larger market with a new identity and owners who likely care more about profits than they do championships.

Very few teams exist in the NBA these days with winning being the top priority for ownership.

Even the best teams have owners that frequently avoid paying the luxury tax or try to shrink their rebuilding timeline in order to get butts in the seats and generate revenue (we’re looking at you, Josh Harris and Co. in Philadelphia).

The Pacers and Portland Trail Blazers are the two teams that come to mind when one thinks of “pure basketball.”

I won’t sit here and paint the ownership groups in Portland or Indiana as being philanthropic for owning these teams. Undoubtedly they have financial motivations, but these teams are always competitive and willing to get things done the right way. Portland being the only team willing to take a chance on the ousted Carmelo Anthony is a good example of the unconventional risk they will take to win

These teams understand how to build a team because the top focus is quality basketball, not dollar signs. The fanbase is seen as a valuable and intrinsic part of the organization, not profit margins.

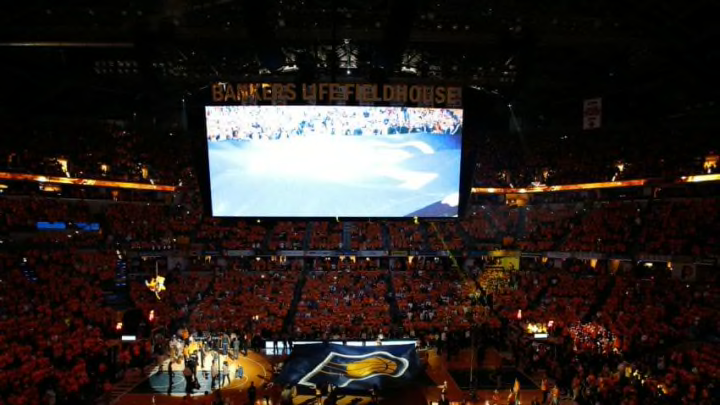

Indiana is unique. One of the midwestern teams, much of the fanbase is comprised of fans who live in small communities throughout Indiana. It’s a slower pace of life, one reflected in the Pacers bottom-third pace of play.

It might not have been this way for the Pacers. They might have been flipped and turned into the racy, quick-buck team that many organizations are today.

They were so close to being that.

In fact, the Pacers were so close to not even getting past the ABA/NBA merger.

When the leagues merged, four ABA teams came over — the Nets, Nuggets, Spurs, and Pacers.

The Kentucky Colonels were originally going to be one of the four teams, which would have squeezed the Pacers out. The Chicago Bulls blocked the Colonels from joining as they owned the NBA rights to one of their players, Artis Gilmore. So, the Pacers got the call.

There was a steep price for the Pacers to get into the NBA — $3.2 million (which today translates to a value of about $15 million). Other teams had it worse, the New Jersey Nets had to come up with nearly $5 million on top of their NBA league dues to pay the New York Knicks for infringing on their turf and had to trade Julius Irving to the Philadelphia 76ers to come up with the cash.

Indiana was already low on cash at this point, but made by for a season. Slick Leonard described the NBA’s financial demands to join as a “massacre.”

The situation would grow dire by the summer of 1977, so dire that if the Pacers weren’t able to secure 8,000 season tickets for the following season, the team would need to be sold and likely moved to a more profitable location. Cash had run out. The well was dry.

Faced with impending doom, the Pacers needed to find a creative way to make pro basketball work in a smaller market. They had to do something different to generate the necessary capital.

The answer they landed on? A telethon.

Yes, the classic route of fundraising typically used for charities or non-profits is how the Pacers decided to save their team. After the NBA’s buy-in costs depleted the team’s usable cash, they needed to sell those 8,000 season tickets in a pinch to gain enough cash to keep things running ($2 million) beyond 1977.

The solution came from Slick’s wife, Nancy Leonard, and people were skeptical of the idea, in part because it felt so off-kilter for a sports team to put on a telethon. Sports teams aren’t supposed to patronize in that way.

But people responded. They showed up and gave what they had, whatever it was. A reflective IndyStar article describes the scene as such:

"Factory-working men with nothing more to give than $5 or $10 bills showed up still greasy in their uniforms. Children sidled in shyly to hand over coffee cans filled with pennies and nickels, money they scrounged up going door to door."

According to the article from IndyStar, the team had sold just 6,700 tickets with two hours remaining in the telethon. Leonard, still coach of the team and host of the 16-hour telethon, would leave victorious with 8,028 tickets sold.

But the real victors were the fans and people of Indiana. It’s a story of the common man making clear what is for him and keeping it in his control. Even more, it’s a clear example of how a community can rally together and move synchronously toward a common goal.

We are nothing more than the congregation of our people. And though these days we can’t physically congregate, with coronavirus gripping our world and causing mass fear and anxiety, these stories of community remind us we can do anything when we work together.